I decided that I would not release my entry into the Cursed Conlang Circus, because there is so much happening and I lost motivation to make a video about it. Existential burn-out leaves you with not just a lack of motivation, but one rooted in a sense of disillusionment, like “What’s the point in doing it when it won’t benefit me immediately?” I’ve had this type of mindset from the moment I was an English graduate student onwards.

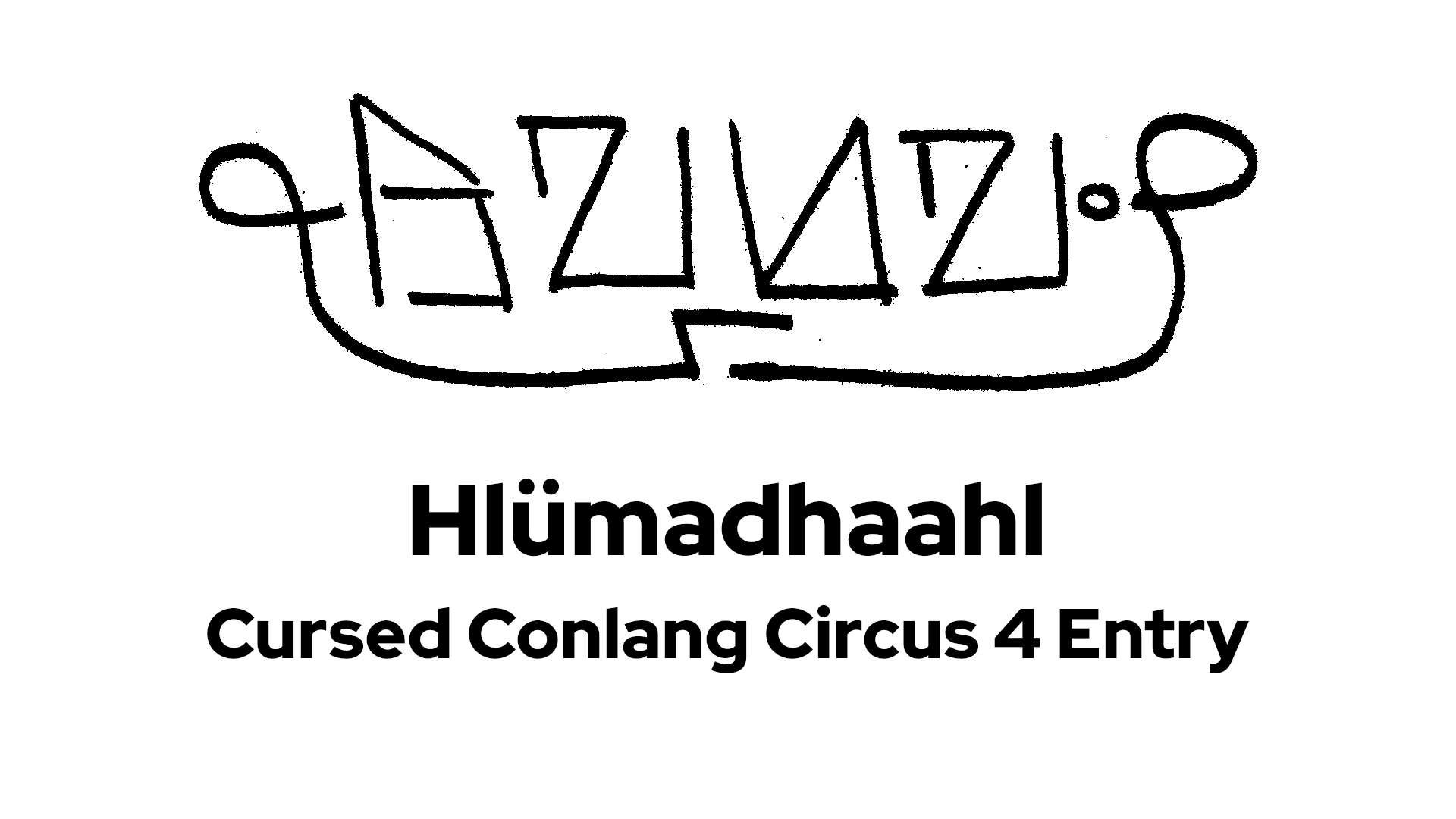

Cursed Conlang

This was my inclusion into the fourth installment of the Cursed Conlang Circus hosted by Agma Schwa. This is the Hlümadhaahl language spoken by the snake-worshipers.

Here’s the format of the video. I’m grateful that Agma Schwa extended the explanation part to 30 minutes maximum, since it was difficult for me to condense my previous entry to 10 minutes.

It doesn’t matter to me whether I win or not, rather I want to partake in this competition to get some clout. Also, I have colored some words green. Those will be important for the end of the video. I also listed my sources in the description.

Basics

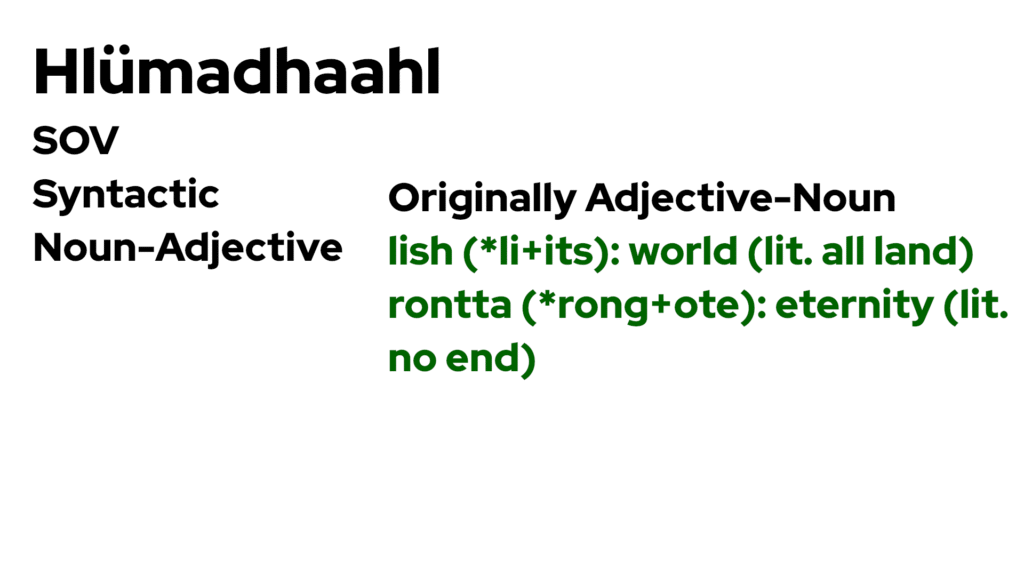

Hlümadhaahl is an SOV Syntactic language, where the adjectives come after the nouns they modify. Of course, the protolanguage behind Hlümadhaahl was originally Adjective-Noun, meaning some of the words in the lexicon reflect this fact.

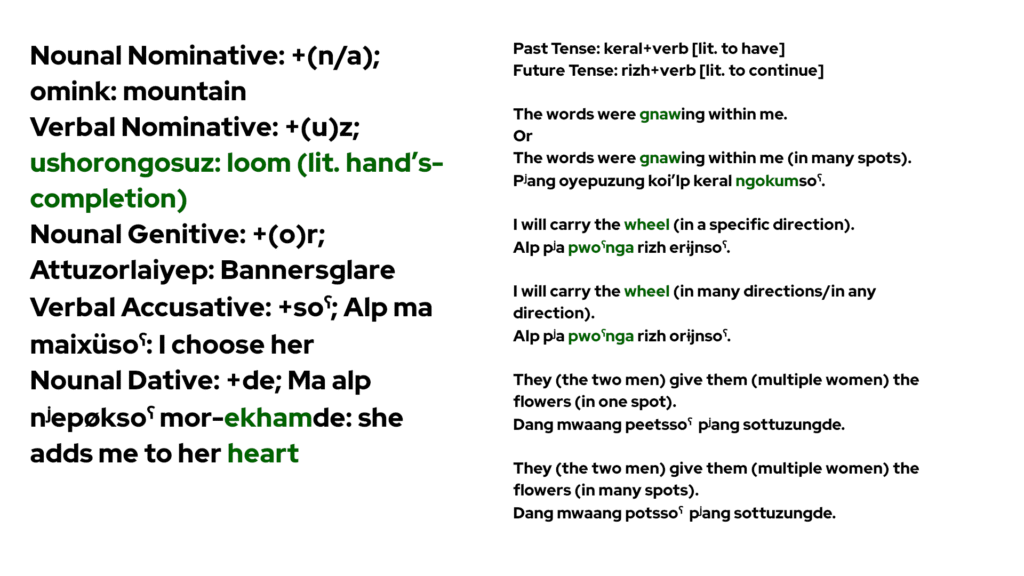

There are declensions that affix either to nouns or to verbs. You can even find a calque translation of my channel name.

As far as past and future tense, the language makes use of the verb “to have” in its infinitive form as an auxiliary verb to form past tense, and the infinitive verb “to continue” to form the future tense.

Verbs tend to be divided between unidirectional and multidirectional, meaning that the verbs determine the direction that the subject makes either itself or with the object. Unidirectional verbs retain their default morphology, while multidirectional verbs require a morphological shift by replacing the first vowel with the back mid vowel (o). It is possible for a verb with a default first back mid vowel to refer to either one direction or multiple directions, and you simply need context to discern the difference.

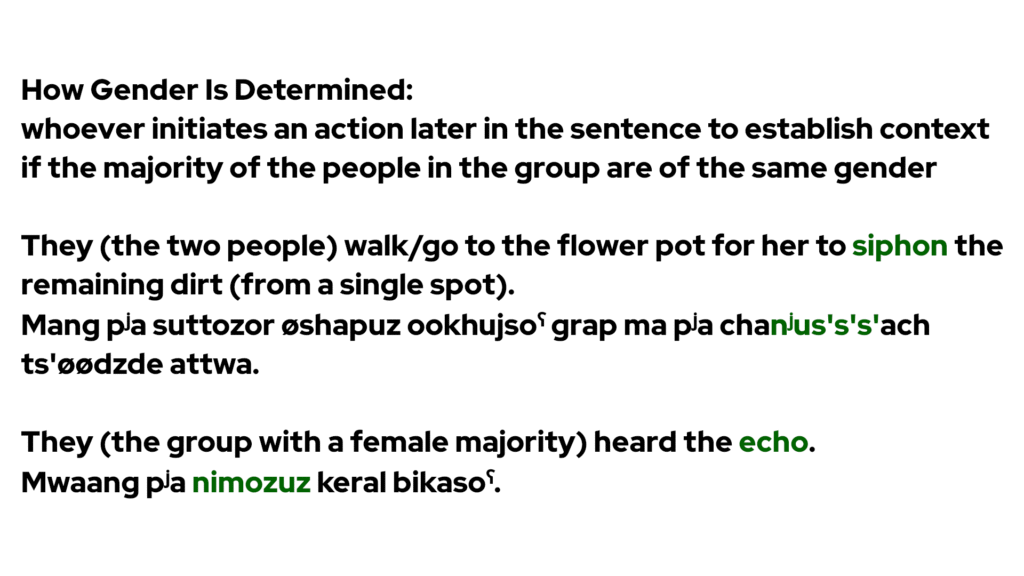

If there is a dual pronoun involving more than one gender, than the specific gender would refer to whoever initiates an action later in the sentence to establish context. If it involves a simple sentence without any further context, the listener relies on the previous dialogue for context. If the majority of the group belong to one gender, then that gender pronoun is used.

Phonology

It has a simple labial consonant system, since it only uses the voiceless plosive labial (p) and the voiced nasal labial (m). Of course, they are modified by either palatalization or labialization. The voiceless dental plosive (t) and the voiceless alveolar plosive (ts) are used a lot, including being the only consonants that can be ejective. There is a more universal usage of the aspirated geminates, but that’s for later in the video.

It uses lots of vowels that can be lengthened or pharyngealized. There are also a few diphthongs that mostly appear at the middle or the end of a word.

Lexicon

Through the Pareto Principle and Morris Swadesh’s list of basic English words, I started with translating more than 100 commonly used words in the English language, which are simple verbs, simple nouns, pronouns, prepositions, questioning words, and conjunctions. Of course, I started with a Proto-Lishkhakʰup language, then transferred them to the present language. There are plenty of diachronic changes to the phonology, which include simplifying the labial consonants and replacing the glottal stops. Not all of these words will appear in the ending sample, but they did help provide a foundation for more abstract, complex words.

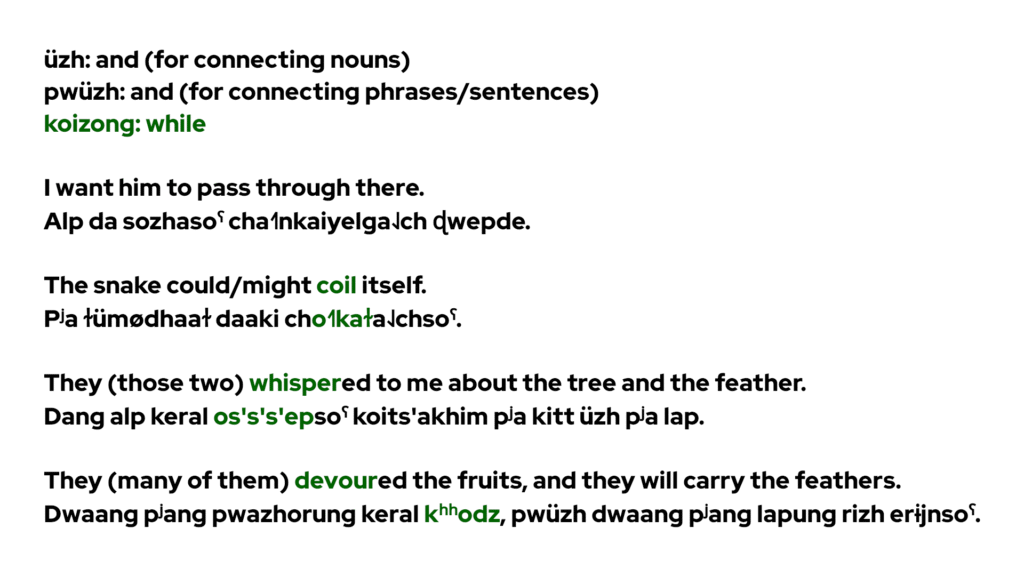

The more complicated aspects of the grammar include hypotheticals and the subjunctives. There are also two words for “and” which include an “and” used for connecting nouns, while another “and” is used for connecting phrases and sentences.

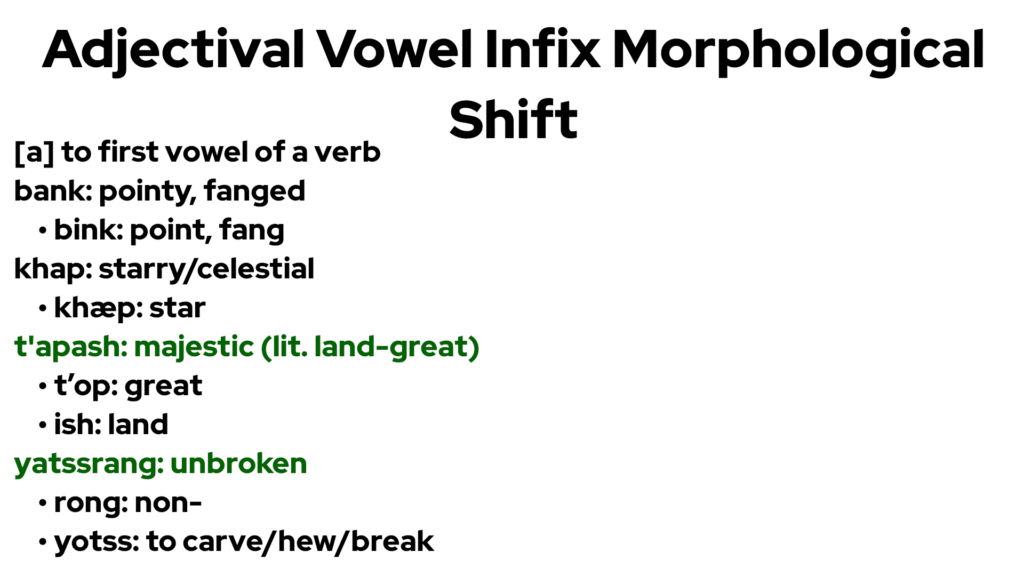

Adjectival Vowel Infix Morphological Shift

In order to create adjectives, the language uses an infixed vowel morphological shift. Typically, it involves taking any word and infixing the open central vowel (a) in the first vowel of a word, whether noun or verb, to form an adjective. I differentiate between adjectives and genitives in the sense that genitive words imply a possession of an object word, while adjectives describe the essence of the object word.

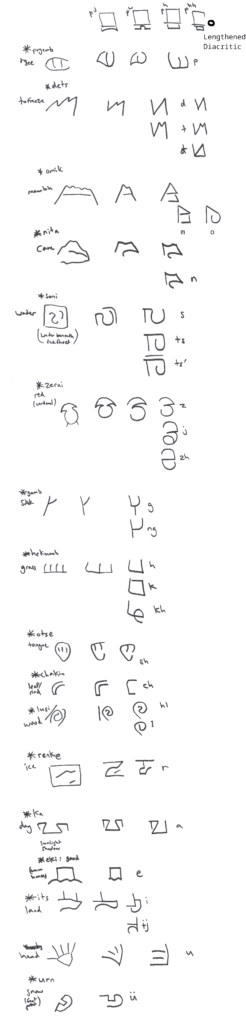

History And Script

I’ll be brief on the history.

Basically, the Hlümadhaahl, literally meaning “snakish,” zealously worship snakes to the point they become an important recurring symbol throughout their culture. They are a dominant power in the world of Lishkhakʰup.

Their alphabetic script was directly inspired by divinations foretelling they would reach outer space. The symbols were directly inspired by the winter landscape since winter is the ideal time for their study.

The most central symbols for some cases were inspired by divinations based on snake curls. They are the subjunctive case, the vocative case, and the agentive case. I will discuss those specific cases later in the video.

Why Is It Cursed?

So now I have to ask what would make the Hlümadhaahl language part of the Cursed Conlang Circus.

Palindromic Circumfix Case Clusters

Since eternity would play a role in the language, then it would make sense to have a set of prefixes and suffixes that are palindromes. This is to represent continuity. This is of course where some of the circumfix case clusters have their own logographs resembling the Ouroboros, which differ based on shape and location, either above or below the word.

There is a vowel tonal system used only for the case clusters. The agentive case uses the down-to-up tones, while the subjunctive case uses the up-to-down tones.

The language uses existential sentences when it evokes a noun in an existential sentence like “What a prosperous land!” by applying the vocative case to the pronoun indicating the noun itself. It would translate to roughly mean “Verily! It is a prosperous land!”

Xenoextremities

There are also degrees that can roughly be translated among Earth people as equivalent to real-world languages. I call these the xenoextremities, meaning components of the language that are expounded upon ad absurdum. This can range from phonology to grammar.

In my case, there are three degrees of xenoextremities within the Hlumadhaahl language:

- Ultratsakhur Proximal Genitive: has a elements similar to the Tsakhur language that expound upon the genitive and some of the phonology.

- Hyperlingala Sentence Connections: Features of the Lingala language used to create large sentences also push the limit but more so.

- Turbobasque Subjunctives: The most accelerated element of the Hlumadhaal language uses the Basque language’s subjunctive and a few sounds.

Ultratsakhur Proximal Genitive Cases

The Tsakhur language, as a Caucasian language, already has a complicated grammar structure, but what if the genitives were made more complicated? That is the phenomenon seen with the Hlumadhaahl. While the Hlumadhaal grammar is not absolutive-ergative, it does differentiate genitives in subject and object nouns, in human and nonhuman nouns, and in singular and plural nouns.

In order to expand upon the genitives, the genitives are differentiated based on proximity. There are genitive cases that refer to various degrees of proximity, from very close to a foreseeable distance to far away out of sight to referring to either fiction or a memory. These proximal genitive cases are distinguished based on stem augments rooted in location protowords.

Hyperlingala Sentence Connections

.

Forms of “and”

for

therefore

with

[Slide 17]

Turbobasque Subjunctive Subordination

The Basque language uses the subjunctive case for subordinating clauses. Such as in the case of the sentence:

“He orders them (the many people) to drink the red water.”

“To drink the red water” would be considered the subordinating clause. It would be considered subjunctive in the sense that it refers to an anticipated, hypothetical scenario.

However, Hlumadhaal goes further than that and refers to multiple subordinating clauses that truly meddle with hypothetical scenarios. They are in adjectival form modifying the subjunctive clauses, making them adverbial in a way, such as ones that last a long time, involve a planned event in the future, involve an event where other options have been exhausted and this is the only option left, and a comparative clause.

Geminate Verbal Derivation

While verbs often distinguish between being unidirectional and multidirectional, the derivation changes when the beginning consonants of a verb become aspirated geminates. While aspirated geminates are used in Cypriot Greek, they are used in Hlumadhaal to intensify the meaning of the original verbs. While the aspirated consonants are already a feature for the voiceless velar plosive (k) and the voiceless velar fricative (x), the aspirated geminates would exist for more specific words.

Snake Phonaesthetics

The Hlumadhaal language uses the phonaesthetics of snakes into their language. You saw this with the circumfix clusters, and the speakers expand that upon the rest of the language.

- Onomatopoeia: snake sounds

- Phenomime: snake movement

- Psychomime: mystery/uneasiness

Phonaesthetic Verbal Derivation

The Hlumadhaal have a way of employing onomatopoeia into their language. Whenever they want to create a verb that implies mystery or something small enough to hide behind blades of grass, they employ a Triple Ejective Voiceless Dental Fricative cluster, inspired by snake movements and sounds.

So now we come to the translation, which is:

Translation

What a majestic serpent—surely it won’t weave itself into the loom of infinity, nor coil into the wheel of endless ruin and rebirth… OH MY GOD—ITS JAWS CLOSE UPON ITS OWN FLESH. Fangs stinging deep into its own tail, it gnaws its bones as if they were the ribs of time itself; it drinks its own marrow as if siphoning eternity.

A beast both devourer and devoured, a whisper swallowed by its own echo—slithering Tail-Eater! Truly a testament to the unbroken dirge of time, now and forever curled in my heart and the heart of the world.

Chach ya ɫü˨˩mødhaa˧˥ɫ t’apash khrosoˤ—A amaki rong cha˧˥rizha˨˩ch pʲonzsoˤ koi pʲa ronttar-ushorongosuzde, riprang cho˧˥kaɫa˨˩ch koi pʲa pwoˤngade nʲu nirɫuzor-rantta üzh loikhizzan-rantta.

[What a majestic serpent—Perhaps it won’t weave itself into the loom of infinity, nor coil into the wheel of endless ruin and rebirth.]

Ɖ˧˥OⱢÜ˨˩LAAˤKÜ˧˥ⱢO˧˥Ɖ—AR KT’IMISUNG AR ZHUZSOˤ-AKI OKAⱢ RUNS, koizong pʲang bonkungde ar linsde-aki, koizong a ar miˤnsung ngokum chø˧˥shapsoˤ˨˩ch-ɖenkam pʲang miˤnsɖarungde nʲu ekude amaki.

[OH SLITHERER—ITS JAWS CLOSE UPON ITS OWN FLESH, while the fangs sting deep into its own tail, while it gnaws its bones as if forming the ribs of time itself.]

A araki mizol øzapikisoˤ cha˧˥nʲus’s’s’a˨˩ch-ɖenkam ronttade.

[It drinks its own marrow as if siphoning eternity.]

Ya droor ɫü˨˩kʰʰadzü˧˥ɫ üzh keral-kʰʰadz laj, ya os’s’s’ep keral-rangi mʲønk araki nimozuzde—Ɖo˧˥Linsor-Ɫü˨˩kødzü˧˥ɫ Lako˧˥ɖ!

[A beast both devourer and devoured, a whisper swallowed by its own echo—Oh, Slithering Tail-Eater!]

Koiriiluz ya pʰʰwoyapuz grap lonuzor-gʰʰakhi-yatssrang nʲu eku, keral-okaɫ zang üzh rantta koi’lpor ekhamde üzh pʲa lishor ekhamde.

[Truly a testament for the unbroken dirge of time, now and forever curled in my heart and the world’s heart.]

Gateway Sources

- Perplexity.

- Wikipedia.

- Wiktionary.

Primary Sources

- Dubrovskaya, Olga and Evgeniya Bondareva. “Preservation of the Shor Language of the Small People of Kuzbass as a Component of Russian Coal Cluster Sustainable Development.” E3S Web of Conferences 278. SDEMR-2021. 2021.

- Haase, Martin. “Tense and Aspect in Basque.” Bamberg: Otto-Friedrich-Universität, S. 279–292. 2023.

- Honkasalo, Sami. “Kazakhstani Gansu Dungan as a Contact Language: An Analysis of Russian Influence.” University of Helsinki. Languages 2024, 9(2), 59.

- Omniglot.

- Basque language and alphabet.

- Croatian language, alphabet and pronunciation

- Dungan Language.

- Greek language and alphabets.

- Lingala language and alphabet.

- O’odham Language.

- Romansh Language and Alphabet.

- Russian Language and Alphabet.

- Shor (Шор тили) – language, alphabet and pronunciation.

- Tsakhur Alphabet, Pronunciation and Language.

- Newman, MEJ. “Power laws, Pareto Distributions, and Zipf’s law”. Contemporary Physics. 46 (5). Pg. 323–51. 2005.

- “Pareto Principle (80/20 Rule) & Pareto Analysis Guide”. Juran.

- Pareto, Vilfredo; Page, Alfred N. “Translation of Manuale di economia politica (“Manual of political economy”).” A.M. Kelley. 1971.

- Schulze, Wolfgang. “Tsakhur.” Languages of the World: Materials 133. Lincom Europa. 1997. Pg. 30-1.

- Swadesh, Morris. (1952). “Lexicostatistic Dating of Prehistoric Ethnic Contacts.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 96, 456–7.

- “The Shor Language.” Endangered Languages of Indigenous Peoples of Siberia.

- Thornton, Fr. James. “Vilfredo Pareto: A Concise Overview of His Life, Works, and Philosophy.”

- Tiffany, Chase. “Linguistic Features.” Romansh Language.

- Zepeda, Ofelia. “A Tohono O’odham Grammar.” University of Arizona Press. 1983.

It’s a shame you lost motivation – existential burnout is definitely a tough thing to deal with creatively. I found some interesting perspectives on managing that kind of thing while researching a similar project, and https://tinyfun.io/game/dog-racing-master-game had a surprisingly relevant section on pacing and avoiding overwhelm.